6 March 2023

Foregrounding a human rights based approach

A guide to prioritising people in urban African sustainable development projects

Placing people at the centre of development policies and programmes is key to effective sustainable development. Cities are complex systems, and changing just one of their components, from food distribution networks and energy grids to transport and greenways, impacts others. Designing solutions that take these interconnections into account is critical to sustainable development, and weaving a people-centred approach into development projects and programmes is crucial for bringing about systemic change.

This is why the five ICLEI pathways, towards low emission, nature-based, equitable, resilient and circular development, are designed to work together, and embedding a people-centred approach into these pathways at ICLEI Africa means that we:

Promote a human and gender rights-based approach to climate, nature, urban systems, etc;

Ensure that socio-cultural and socio-economic aspects are prioritised in urban development processes to ensure that people are not disenfranchised of their rights in the process; and

Foster a bottom-up approach where minorities and vulnerable groups are involved in decision making processes to ensure better outcomes for all.

I learnt something yesterday that I’m definitely going to take home, which is the fact that human rights are intertwined with urban natural assets.

Human rights as an entry point for valuing nature

Keenly aware of the disparities Africa faces in its economic and political placement within the global community, ICLEI Africa is embracing a people-first, human rights based approach in its work in African cities. This prioritises the lives and livelihoods of people in our cities and places a specific emphasis on vulnerable groups – including children, women, youth, the disabled, aged, indigenous communities and LGBTQIA+ communities.

Since 2014, ICLEI Africa has been successfully developing, enhancing and implementing the Urban Natural Assets (UNA) programme, funded by SwedBio. At its core, it aims to support local governments in Africa to address the daily challenges they experience around protecting and revitalising their urban natural assets – to improve human well-being, contribute to poverty alleviation and build climate resilience, through integrating nature-based solutions (NbS) into land-use planning and decision-making processes at all levels of government. The focus of this latest iteration of the programme, UNA Resilience, is integrating a human rights based framework across its three interlinked pillars of work – governance, planning and finance.

Introducing rights into the discussion about the environment is a useful entry point to explore nature-based challenges and their consequential threats for communities. It provides an opportunity to explore how human rights are contingent on protecting the natural environment in urban spaces. It also creates a space for embedding indigenous knowledge systems in how we protect and revitalise urban natural assets. Furthermore, it is aligned with the conceptual framework of integrating human rights into the Kunming-Montréal Global Biodiversity Framework. The hypothesis is that the stronger the understanding of the connection between nature and human rights, the more likely stakeholders within communities will become champions for nature, restoration and NbS. In practical terms, this means that through the duration of this phase of UNA, a human rights based framework is being adopted – from the constitution of the internal UNA team to the project deliverables and implementation, human and gender rights are central considerations.

Many practitioners in Africa and other global South regions encounter hesitance in the onboarding of human rights based approaches when working with communities, for a variety of reasons, including:

The assumption that human rights are detached from many deeply held traditional and customary norms and values;

Religious systems and beliefs resistant to change;

Lack of education and awareness about the value of fulfilling human rights;

Lack of belief in the legal system to entrench, guarantee and protect the rule of law and human rights;

A widely held belief that human and gender rights discourses are very North-facing and do not resonate with African/other global South perspectives. In order to account for these limitations, the UNA team used participatory methods to introduce human and gender rights discourses to project participants, within a learning exchange environment (termed learning labs) – being guided from understanding, to accepting and fully embracing, a human and gender rights based approach in urban nature.

Here’s how they did it:

1. Vernacularisation of human rights

Introducing human rights as part of the fabric of African societies, through for example, contextually relevant folklore analysis, enabled participants to begin making connections between natural assets, their role and importance, the human rights angle for protecting nature, and the threats to natural assets in cities, from climate change.

The key take home for participants was ‘you have human rights because you are human’ and that ‘although it may have been iterated differently, human rights have always existed in our societies’.

2. Onboarding the human rights discourse

Having created a space where participants could relate to the concept of human rights as inherent to the human condition, and in our societies predating colonialism, a deepdive into the current framework of human rights at international, regional and national levels was necessary. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, as well as local constitutions were used to explain key concepts on human rights. Furthermore, it was necessary to ground the participant’s understanding in the balance between rights and responsibilities, and the roles played by various stakeholders in furthering human rights, with a particular emphasis on the rights aligned to the environment (such as the right to a safe, clean and healthy environment).

An interactive activity helped participants identify duty bearers and other responsible stakeholders in the fulfilment of their rights, while identifying intersecting points of personal responsibility. Some stakeholders identified by participants through this interactive session included; government officials, law courts, police and para-military agencies, communities, traditional leadership, family, religious bodies and individuals.

3. Prioritising representation

Ensuring diversity of representation in sessions is crucial to gathering multiple inputs and building a holistic perspective. Avoiding using highly technical terminology and focusing on easy to understand, non-discriminatory language helped to ensure that the sessions were inclusive for all. Building on representation within learning labs, is representation beyond them – in this case, more general participation in the preservation and restoration of urban natural assets.

During engagements, participants identified ways in which indigenous knowledge holders, youth, women and other diverse groups could be involved in the processes of restoring and protecting urban natural assets. Developing mentorship or educational programmes, establishing environmental clubs, or incentives for the involvement of women, youth and vulnerable groups in urban natural assets protection and restoration are promising approaches.

Representation also means the inclusion of indigenous knowledge systems, and this was key to UNA as one the negotiating points of the Kunming-Montréal Global Biodiversity Framework. Hence the constitution of participants at the learning labs included traditional leaders, an important strategy to help embed a human rights outlook within the broader framework of the community

4. Understanding and breaking down power dynamics

Facilitators should always be aware of the power dynamics at play within the settings in which they work, and consciously try to address and overcome them. Often, it is the same people – usually men and/or people in positions of authority, such as traditional leaders, city officials etc. – who lead discussions that can make others feel intimidated, especially those with less technical knowledge. It is therefore important to create space for community members to share their inputs in these kinds of dialogues. This included directing specific questions to them or having side conversations during the learning labs to get their input, and encouraging their contribution to the discussions.

This also extends to the facilitator’s understanding of their own positionality within these settings, and altering their positionality deliberately to one of co-learning. It is useful to reiterate to participants the attempt to create a space for mutual learning and co-production, and that participants and facilitators may have differing views; however, everyone should be open to listening, learning and unlearning.

5. Onboarding gender rights

Gender rights are central to the fulfilment of other human rights, and sensitivity is critical in the onboarding of gender-related discourses and implementing strategies in deeply patriarchal communities. Facilitators must be aware of the need to create safe spaces for challenging gender biases, without placing participants in precarious positions where they are exposed to possible harm and/or retribution.

To contextualise this discussion, examples were used to ground the understanding that the fulfilment of the rights of others is contingent on the fulfilment of women’s rights.

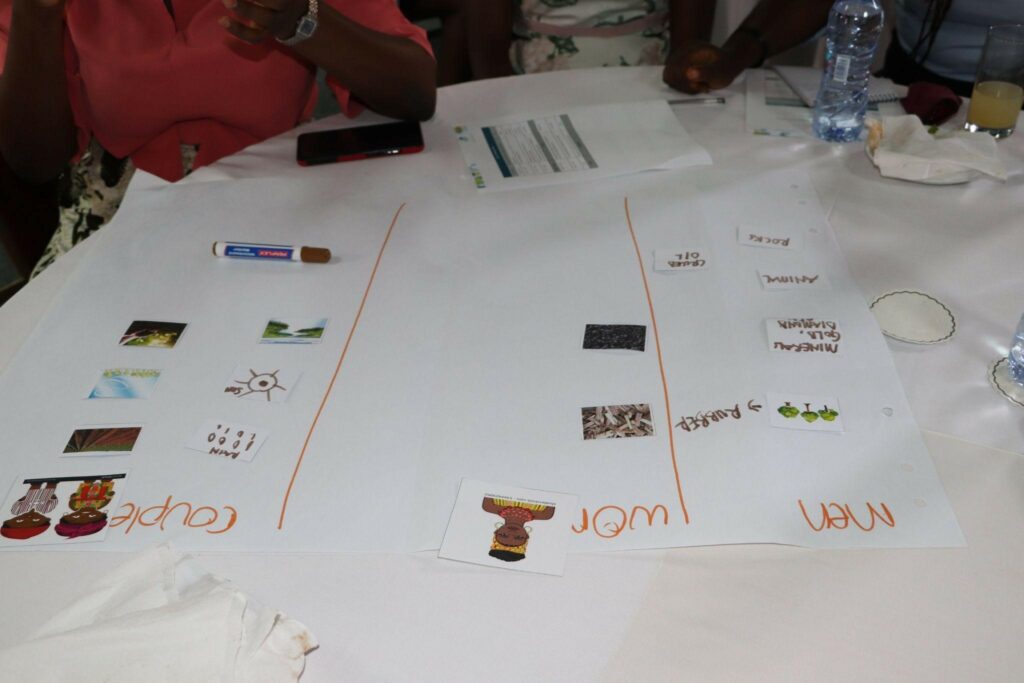

In addition to this, participants were taken through an interactive session on the allocation, use and control of natural resources and how this affects women’s abilities to participate in forums of decision making, which was followed by a facilitated discussion on natural resources control and ownership.

Since gender rights discourses are particularly sensitive in historically patriarchal contexts, there is a need to build incrementally towards discussing the “why” of gender rights. The processes described above were undertaken over the course of an entire year.

Having built the necessary foundation, the final session for the year was then able to approach the idea of dismantling gender stereotypes and bias.

Human and gender rights as a golden thread in mainstreaming

People-first means people first – not the project, nor the plan or the proposal. A human rights based approach has to start at the human level, and constantly return to it – from the beginning to the end of a project and beyond. Using participatory methods, and meeting people where they are, is one way to ensure all stakeholders can be included and brought along in the process toward achieving the project’s core aims.

Truly embedding a human rights based approach entails interweaving it across all aspects of a project – it cannot be treated in isolation. This is an approach worth scaling to other African and global South communities, with our shared learning experiences across these and other countries serving to further strengthen and establish this framework as critical for people-centred project design.

It starts with capacitating the internal project team, to help onboard this approach across the various facets of the project, and is followed by integrating it across interactions, methods, outputs and deliverables. Project leads should constantly be seeking avenues to embed and mainstream this approach, and to better capacitate stakeholders to understand and integrate this framework into their work as a matter of necessity and practice – not merely preference.