12 June 2023

Practising Participation: The human rights-based approach in action

A people-centred approach takes the needs of people into account, first and foremost. But understanding what people need is not as straightforward as simply asking. There are always countless complexities and dynamics at play – language, expression, power, familiarity, location, customs. The key is to create spaces where people feel that they can express themselves, but also that they are being heard.

What are participatory methods?

The UNA Resilience project has long been a proponent of participatory methods, weaving them into the programme’s design in various cities, throughout its almost decade long history: an urban tinkering walking workshop in Kisumu, Minecraft in Addis Ababa, photovoice in Lilongwe. While different in execution, these methodologies have several things in common:

- They are inclusive and encourage the inclusion, or observation, of all voices

- They create room to unveil issues that may otherwise remain hidden to decision- makers, placing great emphasis on local knowledge

- They are generally more creative and encourage participants to explore alternate forms of expression

- They give agency to participants by putting the pen or the mic or the camera in the hands of participants rather than researchers

- The experience of conducting the participatory method is often as important and revealing as what is expressed during the session itself

- They ensure ordinary people can be actively involved in decision-making on matters which affect their lived realities.

Participatory methods benefit our understanding of what communities truly want and need, and in this way allow practitioners, governments and organisations to co-design programmes that are relevant and have the highest chance of successful uptake by the community. It’s no surprise that when people feel that their voices have been truly heard and considered in designing a solution, they are more likely to take ownership and responsibility for what comes next. And while it may require additional time, intention, effort and consideration to run a participatory session that is truly accessible and representative, it is a crucial stage not just when it comes to implementation, but in the initial research phase as well. You can’t solve what you don’t fully understand.

But in addition to its pragmatic benefits for project design, participation embodies a human rights based-approach. This approach centres people: valuing and prioritising their opinions, experiences and local knowledge – and recognising people identified as vulnerable as well as their interactions within this context. It uses diverse and creative means to break down interpersonal and group dynamics, and overcome language barriers by relying on visual tools. It has the potential to bring even the most vulnerable and ignored voices to light, and include them in the conversation.

A selection of photographs taken by participants at the Cape Coast and Bo City photovoice workshops

The most recent learning lab for the UNA Resilience project focused specifically on employing two styles of participatory approach, and putting into practice the human rights based-approach that participants had up until that point only been engaging with on a theoretical level. By giving participants multiple ways to share their voices, and making the connection between the discussions in the room and the realities on the ground, previously undiscovered challenges and potential opportunities came to light.

After a day of recapping the basic principles of nature-based solutions, attendees (from government officials to community members) stepped outside the meeting room to explore their environment in person and in real time. They visited key sites of human-nature interaction, discussing the relative sustainability and resilience of these systems, and how to improve their management for the future. To overcome inevitable language barriers and power dynamics, and provide an alternative, visual way to capture insights, participants were also tasked with taking photographs. They discussed the significance of their photographs when the group joined back together, allowing new insights and valuable observations to be shared. In some cases, city officials were made aware of simple entry points to implement local programmes.

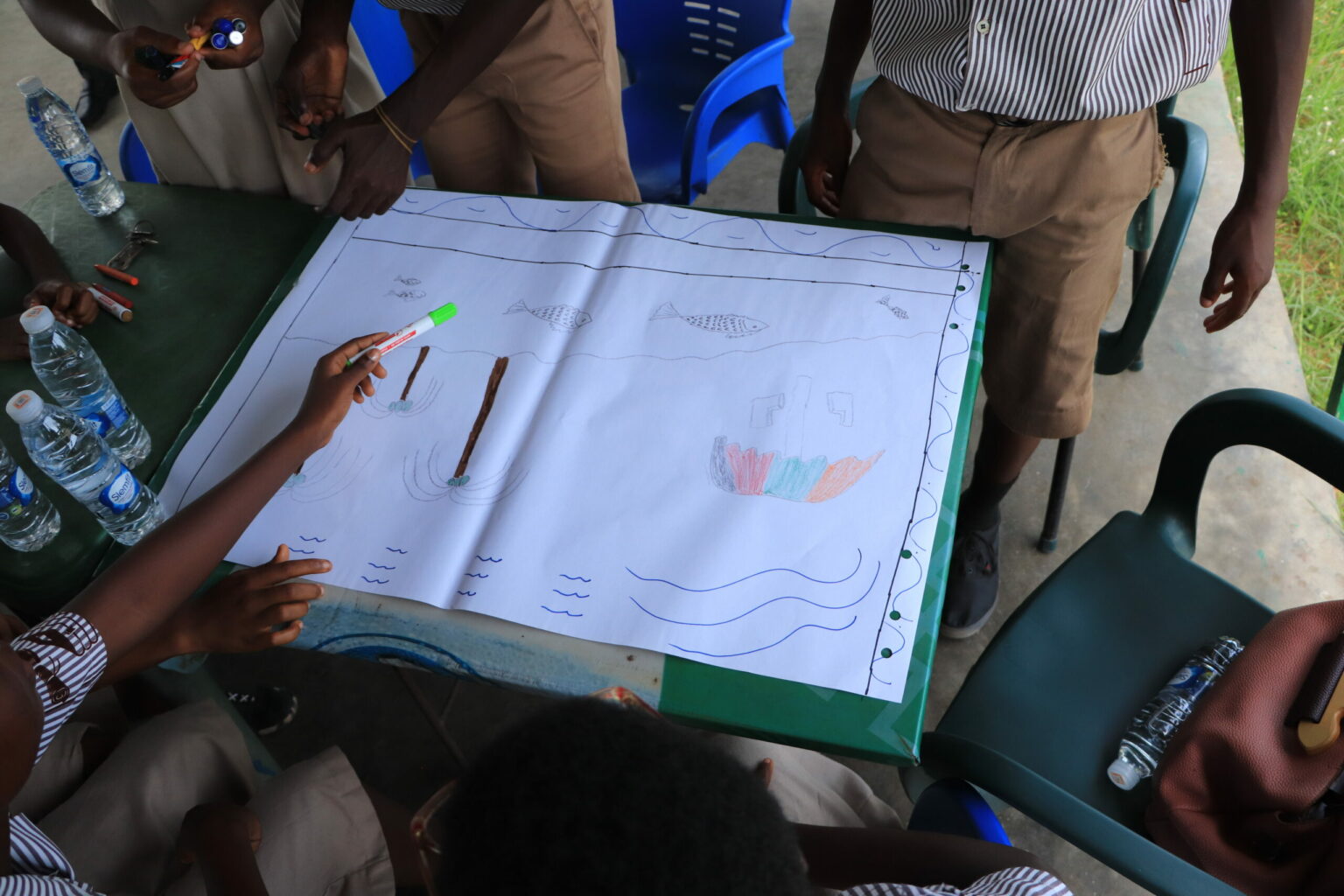

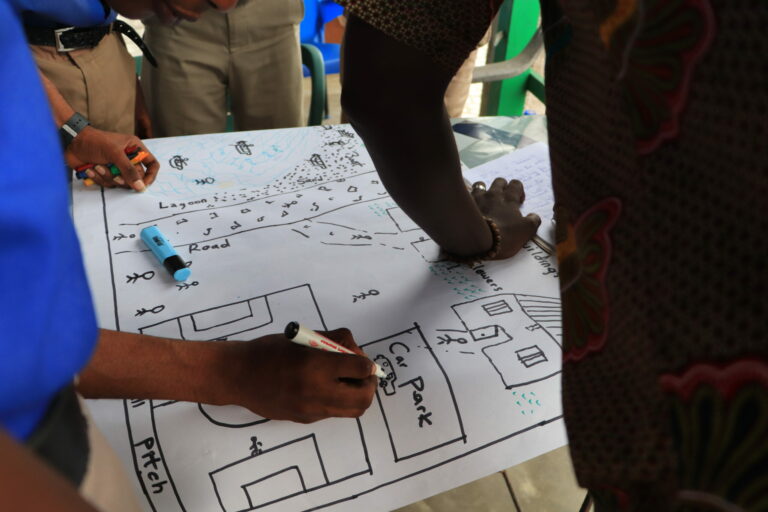

Youth working on their city vision drawings at the UNA Resilience Youth Days in Cape Coast and Bo City

A workshop specifically for the city’s youth was also held, on the final day in both cities. The workshop brought together high school students from a number of local schools to better understand how they imagine the future of their cities in 50 years time, within the context of a discussion around the importance of urban natural assets. In groups, students drew their imagined future – enabling them to participate in the discussion, giving insight into their perceptions of nature’s value and sharing their reflections on their relationship with the environment.

While these methods prove the importance and value of participatory approaches, it must be emphasised that they also embody a human rights-based approach in action, and help to strengthen the understanding of human rights by participants. The discussions and photographs taken during the interventions suggest an increasing awareness of the connection between rights and natural assets, and the role of the urban environment within and beyond its immediate extractive value. The learning lab is one example that highlights the importance of collective engagement and collaboration in driving impactful city interventions, but practising participation should be built into the design of every development project. By bringing multiple voices to the table, in different ways (speaking, drawing, photographing), a more nuanced and accurate depiction of people’s experiences and perceptions, and the city’s opportunities for intervention, is possible. Practising participation is an essential part of bringing socioeconomic and climate concerns onto the same page, and finding not just mutually beneficial but also mutually reinforcing ways forward.