Bridging finance and biodiversity: Crucial steps for African city resilience

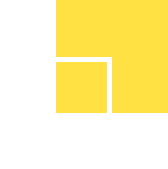

Amidst the escalating challenges posed by climate change and biodiversity loss, African cities find themselves at a critical juncture, where the intersection of finance and biodiversity holds immense significance for resilience. With more than half the world’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) relying on biodiversity and the services it provides, it is imperative to bolster urban ecosystems against environmental shocks. Cities across Africa continue to expand and develop at an unprecedented rate, but the need to protect and manage nature effectively is at the forefront. Biodiversity finance is fast becoming the cornerstone for adopting and implementing effective mitigation and adaptation strategies.

Biodiversity and resilience

Many, if not all, of the resources that humanity uses to sustain itself are derived directly or indirectly from ecosystem goods and services provided by nature. From regulating climate patterns to providing essential ecosystem services, biodiversity underpins the very fabric of our existence and inherently the urban resilience in African cities.[1] However, biodiversity is declining at an unprecedented rate, and is being altered extensively across all spatial scales (locally, regionally and globally). According to the 2023 World Economic Forum Global Risks Report, biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse are one of the ten greatest risks facing our society today. The effects for human health and well-being, societal resilience and sustainable development are considerable and potentially even catastrophic.

In recent decades, there has been a growing concern regarding biodiversity loss and finding means to maintain, restore and protect biodiversity. This has mostly been driven by several global agendas, including the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and commitments made by the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD).[2] In December 2022, Parties to the CBD agreed to the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), a framework that builds on the CBD’s previous strategic plans and supports the achievement of the SDGs. Through four goals and 23 targets, the GBF aims to address biodiversity loss, restore ecosystems and protect indigenous rights by 2030, whilst also proposing to increase biodiversity finance to developing countries, through a GBF Fund.[3] In addition, the framework seeks to engage countries, cities, subnational governments, Indigenous peoples and local communities, industry, women, youth, farmers, civil society and the private sector, to safeguard and sustainably use biodiversity by 2030 and beyond.

The urban challenge

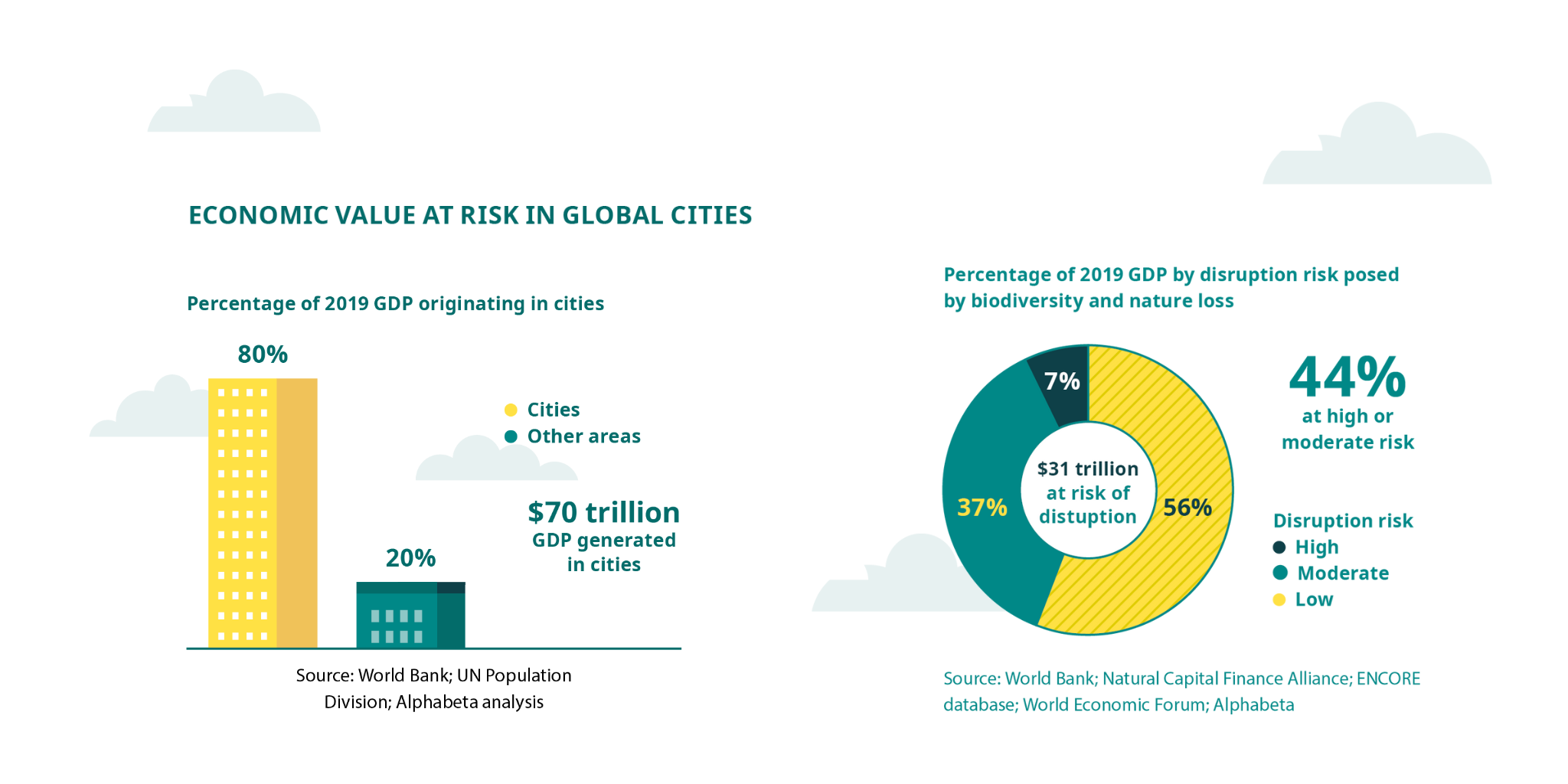

Urban expansion is projected to grow significantly in the next 20 to 30 years, as it is anticipated that up to two-thirds of the global population will reside in urban areas.[4] While cities may occupy just 2% of global terrestrial surface, they consume 75% of the Earth’s natural resources. This pressure on natural resources, ecosystems and the climate will continue to rise with approximately 1.5 million people expected to move to cities globally, every week until 2030. Urbanisation is not globally homogenous, as the most rapid urbanisation will occur within the Global South. While the world’s urban population is expected to increase, almost all urbanisation is expected to occur within low- and middle income countries, and this is particularly true for cities within Africa and Asia, where 90% of this urban growth is expected to occur.[5] Its projected that Africa’s cities will grow by an additional 900 million inhabitants between now and 2050.[6]

The greater the pressure on biodiversity, as a result of urbanisation, development priorities and other drivers, the greater the risk to humanity. Cities are at the precipice of the challenge of climate change and biodiversity loss and will continue to face unprecedented pressure to provide adequate housing, sanitation and ecosystem goods and services to their residents, if adequate measures to halt biodiversity loss and other risks are not addressed with urgency.

What is biodiversity finance?

At its core, biodiversity finance is the practice of raising and managing capital and using financial incentives to support sustainable biodiversity management. Biodiversity finances can come from both the public and private sectors, with the financial resources supporting a range of investments including protected area management, ecosystem restoration and rehabilitation, species conservation and the sustainable use of natural resources.[7] Just like diversifying investments to manage financial risk, biodiversity finance enables us to maintain, manage and protect the diversity of our natural assets – therefore reducing the risks to humanity and increasing resilience to shocks from natural disasters.

As a concept, biodiversity finance has been around for decades and has gained significant traction at a global scale. Furthermore, several financial instruments have been used to support biodiversity, including Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES), biodiversity offsets, green bonds, and multilateral grants. One of the most important aspects however, is that biodiversity finance is critical for delivering the transformative changes needed to halt and reverse the loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services – offering a myriad of opportunities for African cities to fortify their resilience against environmental and climate threats and risks.

The biodiversity finance gap

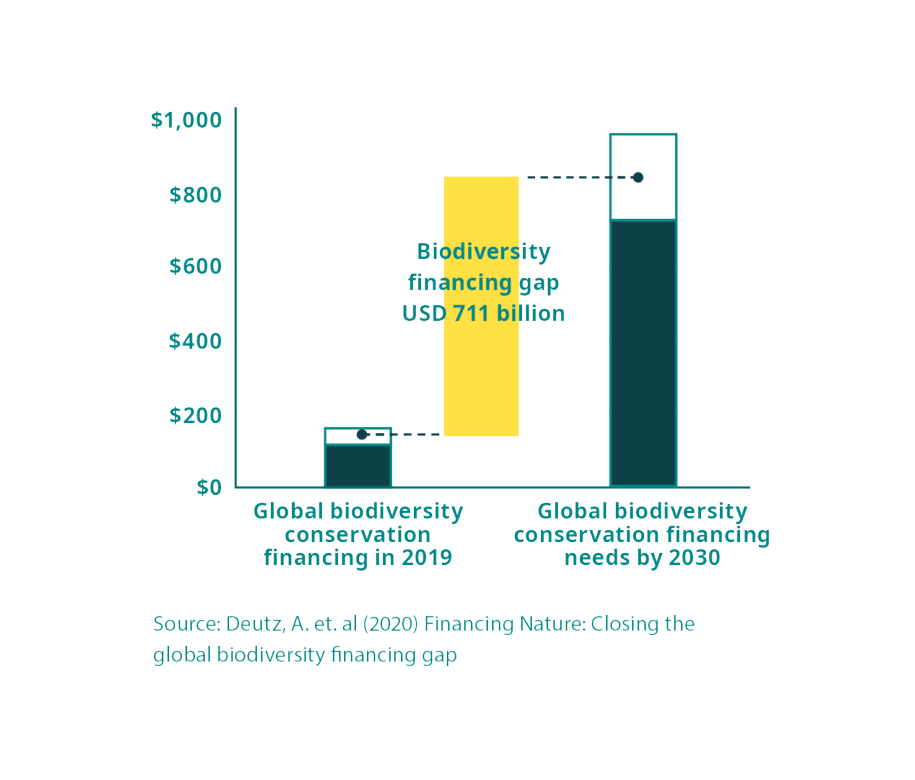

Crucially, the importance of biodiversity finance extends beyond ecological preservation; it serves as a catalyst for inclusive and sustainable development. Between now and 2030, it is estimated that USD 722-967 billion is required per year to prevent further decline and loss of biodiversity.[8] While biodiversity finance flows rose by 2.6% between 2021 (USD 150 million) and 2022 (USD 154 million), finances for biodiversity continue to fall significantly short of the annual biodiversity finance needs required. UNEP’s State of Finance for Nature 2022 report identifies a USD 4.1 trillion financing gap by 2050. If we close the biodiversity finance gap, ecological function can be stabilised by 2030 and increased from current levels by 2050. In addition, with sufficient finance, nature-based solutions (NbS) can provide the means to cost-effectively reach climate, biodiversity and restoration goals and targets.

Given the projected biodiversity loss, it is critical that biodiversity finance flows be upscaled urgently by both public and private actors. There are various tools and mechanisms that can play an important role in closing the biodiversity gap. The Kunming-Montreal GBF Strategy for Resource Mobilisation encourages the use of “innovative” finance mechanisms, solutions and instruments. The Biodiversity Finance Initiative (BioFin – an initiative which began following the 2010 CBD COP 10 in Nagoya, as a response to the urgent global need to divert more finance from all possible sources towards global and national biodiversity goals) has identified 68 different finance solutions that could be used to mobilise financial resources for biodiversity. Not all finance solutions or mechanisms may be applicable to cities or local governments. Applicability is dependent on the challenge or issues needing to be addressed and the desired financial results and impact.

To achieve particular financial results, finance solutions need to consist of several key components. Finance instruments are one of these components, and there are several types of finance instruments that could be used to achieve financial results, each having a different function and outcome. In the Global South particularly, funding has been predominantly grant-based, with 80% of tracked funding coming from grants. Bond mechanisms are becoming increasingly useful in mobilising additional financing for climate and environmental activities. In 2021, however, only 0.8% of green bonds from emerging markets were allocated to nature-related activities, while sustainability bonds only had 4% of key performance indicators related to biodiversity protection. Furthermore, Blue bonds are gaining traction as a debt instrument to raise capital to finance marine and ocean-based projects that have positive environmental, economic and climate benefits. Cities and local governments need to consider not only shifting towards funding from a variety of funders, but also diversifying the types of funding provided through innovative instruments and mechanisms.

Boosting finance and capacity through UNA

There is a strong socio-economic case that can be made for the mobilisation of biodiversity finance. While it has been established that biodiversity and ecosystem services underpin the functioning of the global economy, it is also intrinsically interlinked with overall human health and well-being. This is particularly true within the Global South, which possesses a significant share of unique biodiversity, as natural resources and ecosystem services directly underpin a significant proportion of livelihoods. Leveraged appropriately, biodiversity finance can be a lifeline that can ensure a future where economies, society and nature live in harmony.

In attempting to address the pressing challenges of climate change and biodiversity loss in African cities, initiatives like ICLEI Africa’s Urban Natural Assets (UNA) programme, funded by Swedbio for the past 10 years, stand as beacons of innovation and collaboration. The most recent phase of UNA, UNA Resilience, has worked to equip local governments with the resources, knowledge, and networks needed to navigate the complex terrain of biodiversity finance.

Both Bo City and Cape Coast have undergone comprehensive mapping of their financial landscapes, with the aid of a team of local consultants. Engagements with city officials and pertinent stakeholders were held, and avenues for attracting investments in biodiversity finance were identified. The project unearthed critical information that is being used to shape and refine project concept notes tailored to each city’s unique needs. Moreover, targeted capacity development sessions were conducted with local governments, bolstering their skills to identify and pursue future biodiversity finance opportunities. These efforts, part of a broader series of trainings by the UNA programme, have equipped officials with a nuanced understanding of biodiversity finance concepts and the mechanics of developing project proposals. Complementing these endeavours, the creation of informative materials, including an Infographic, Handbook, and Guide, serve to empower UNA cities and local governments in integrating biodiversity finance seamlessly into their planning and decision-making processes going forward.

Through the capacity-building efforts on innovative financing solutions, biodiversity project development and helping to broker strategic partnerships, the UNA Resilience project exemplifies how cities in Africa could leverage much needed funding for biodiversity, access technical expertise, and mobilise resources to enhance their resilience in the face of nature and climate related risks.

Conclusion

The convergence of climate change and biodiversity loss in cities, especially those in Africa, reiterates the urgency for governments to embrace innovative approaches to finance and conservation. As suggested by BioFin (2018), we need a shift towards a new investment and policy model that better incorporates the economic value and financial benefits of biodiversity and nature, particularly as development demands rise. Cities, as engines of economic growth, are well-placed to raise, generate and sustain revenues but financing of biodiversity is a shared responsibility of government, the private sector, and us all. To ensure the up-scaling and sustainability of biodiversity financing, governance and partnerships between finance and environmental actors is critical.

By harnessing the power of biodiversity finance, cities can chart a course towards resilient, inclusive, and sustainable urban landscapes, where the harmony between nature and humanity thrives.

Download our resources to learn more about biodiversity finance:

References

[1] Dasgupta, P. 2021. The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review Abridged Version. London: HM Treasury.

[2] Elmqvist, T. et al. (2015). Benefits of restoring ecosystem services in urban areas. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability.

[3] https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/cop15-ends-landmark-biodiversity-agreement

[4] United Nations. 2018. World Urbanization Prospects The 2018 Revision.

[5] United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019). World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision, New York: United Nations.

[6] OECD/UN ECA/AfDB (2022), Africa’s Urbanisation Dynamics 2022: The Economic Power of Africa’s Cities, West African Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3834ed5b-en

[7] Driver M. et. al. (2021) Defining the biodiversity economy with a view to developing a Biodiversity Economy Satellite Account: progress from South Africa.

[8] Deutz, A. et. al (2020) Financing Nature: Closing the global biodiversity financing gap.